Welcome to this guide on pornography addiction—a resource built to help you understand what’s happening and find a way forward. If pornography has become a bigger part of your life than you’re comfortable with, know that you’re not the only one facing this. As a clinical psychologist with 15 years of experience, I’ve worked with countless people to address this challenge head-on. This guide lays out the facts: why pornography pulls you in, how it affects your brain and relationships, and what steps can lead to change. Whether you’re here for yourself or someone you care about, my aim is to offer clarity, support, and practical answers. Let’s begin.

Pornography addiction is a psychological struggle where someone feels caught, unable to stop watching explicit material even as it damages their emotional health, relationships, or ability to manage daily life (Privara & Bob, 2023). It’s like other addictions in that it keeps going, even when the person knows it’s hurting them. Experts debate what to call it—addiction, compulsion, or something else—but after over a decade of research (Mauer-Vakil & Bahji, 2020) and my own 15 years treating it, the signs are clear: it follows an addictive path. If this feels familiar to you or someone close to you, there’s hope. I’ve spent years refining a protocol, available at pornaddictionsolution.com, that targets the root causes and helps people move past this—step by step, with real results.

Pornography addiction works by tapping into your brain’s reward system, much like drugs do. When you watch, dopamine—the chemical behind pleasure—floods in, making it feel good (Love et al., 2015). At first, that’s enough. But with time, your brain gets used to it, and the same old clips don’t hit the same way. That’s tolerance setting in, backed by research (Volkow et al., 2011). Imagine someone starting casually—say, a few videos to unwind. Each time, dopamine fires, locking in the pattern. Soon, the effect fades, and they’re searching for something stronger, more intense, just to feel that spark again. It’s a cycle that mirrors how drug doses creep up—and it’s why this can be so hard to shake.

Here’s how pornography addiction tightens its grip, step by step:

Pornography addiction is becoming more common, and it’s not hard to see why. Technology—high-speed internet, smartphones in every pocket—has put explicit material just a tap away (Owens et al., 2012). That ease of access took a sharp turn during the COVID-19 lockdowns, when isolation and boredom hit hard. For many, pornography became a quick fix for loneliness, a trend that spiked across the globe. Since then, I’ve seen more people reaching out for help, a pattern research backs up (Marchi et al., 2021). Pinning down exact numbers is tricky—it’s a private struggle, often hidden—but studies give us a glimpse: up to 74% of men and 41% of women use pornography, with 3-6% crossing into addiction (Zattoni et al., 2020). Men are four times more likely to get caught in compulsive use, though it touches every gender, age, and background. Teens, though, face an extra risk—their developing brains can lock in these habits early, making them tougher to shake later on.

Spotting the signs of pornography addiction is the first real move toward getting help—or offering it to someone who needs it. It doesn’t look the same for everyone, but after 15 years working with clients, I’ve seen patterns that stand out. These are the signals that something’s off, and catching them early can stop things from getting worse. Here’s what to watch for.

Pornography addiction affects the brain’s reward system, a network neuroscience has mapped out to explain why we seek things like food, social bonds, or intimacy. Normally, this system keeps us balanced, but research shows pornography can overtake it (Hilton & Watts, 2011). In my 15 years of practice, I’ve seen how this shift plays out—clients drawn to pornography over other priorities, their brains adapting to favor it. Studies, like one by Gola et al. (2017), back this up with evidence: using fMRI scans, they found that people with compulsive pornography use show heightened activity in the nucleus accumbens—a key reward area—when exposed to explicit material. This response mirrors what’s seen in drug addiction, suggesting the brain rewires itself, prioritizing pornography even when it sidelines relationships or work. These changes reflect a real alteration in how the brain processes reward, a pattern I’ve observed often in treatment.

Pornography addiction reshapes the brain through specific processes—abuse, tolerance, withdrawal, and craving—that tie directly to its reward pathways. These aren’t just behaviors; they’re signs of neurological shifts I’ve tracked over my career working with those affected. Here’s how they play out in the brain:

Pornography addiction hinges on the brain’s reward circuit, a system that steers us toward survival needs like eating or connecting with others. Neuroscience shows this same circuit underpins addiction, and in my 15 years of work, I’ve seen how it shifts with pornography use. Three key areas drive this process:

Pornography alters the reward pathway, shifting how pleasure and desire function in the brain. Two changes stand out:

Pornography addiction disrupts the brain’s dopamine system, altering how rewards are processed and sustaining compulsive use. Three key changes in this system stand out:

These neurological changes explain the difficulty of overcoming pornography addiction. Heightened cravings, learned associations, and reduced self-control form a cycle that feeds itself. Yet, grasping these shifts points to a way forward. Recovery doesn’t demand a full understanding of brain science—much like driving doesn’t require engine expertise. Identifying addiction’s patterns and pursuing targeted support mark the starting point for change and balance.

Pornography addiction can begin as a way to step away from emotional strain or daily pressures. The draw of its vivid content offers brief relief from stress, anxiety, or low mood, serving as an easy coping tool (Hanseder & Dantas, 2023). With time, this turns routine—clients often describe leaning on it to avoid facing what’s underneath. That reliance builds a cycle, where pornography becomes the go-to shield, delaying any real resolution of the underlying issues.

Trauma and mental health conditions—like depression, anxiety, or OCD—often intertwine with pornography addiction, amplifying its force (Shrivastava et al., 2022). Early experiences, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, or neglect, leave lasting marks, increasing the likelihood of turning to coping methods that don’t heal (Sahai & Narang, 2023). Pornography can become one such method—a way to ease pain or sidestep unresolved emotions. Research shows this pattern: those with trauma or mental health struggles may use it for temporary comfort, which strengthens the habit over time. This link highlights why addressing the root issues matters as much as the behavior itself.

Triggers and cravings fuel pornography addiction, acting as psychological cues that sustain the behavior. These factors—external events or internal states—ignite the urge to use, often rooted in habit or emotional need. Recognizing and managing them shifts the focus from reaction to response, a key step in addressing the addiction’s hold (Moynihan et al., 2022).

Triggers are situations or cues that lead to pornography use (Moynihan et al., 2022). They can be external—like suggestive ads, online content, or specific settings—or internal, such as stress, loneliness, or boredom. Identifying these is essential to interrupt the addiction’s pattern and find better ways to cope. Take someone after a long workday, feeling worn down—stress becomes an internal cue, nudging them toward pornography for relief. Or picture scrolling social media, where provocative images pop up, sparking the same urge. These examples show how triggers, inside and out, keep the behavior active until they’re addressed.

Cravings are a powerful urge to use pornography, tied to the brain’s reward system and shaped by conditioning (Love et al., 2015). Each exposure releases dopamine, linking the content to pleasure and strengthening that connection over time. This creates an automatic reaction—visual cues like a screen, or emotional states like stress, can set it off. Studies show this sensitivity to triggers grows with repetition (Robinson & Berridge, 2008), increasing the desire even as the pleasure fades. That fading effect often pushes people toward more intense material to recapture the initial response, locking in the cycle further.

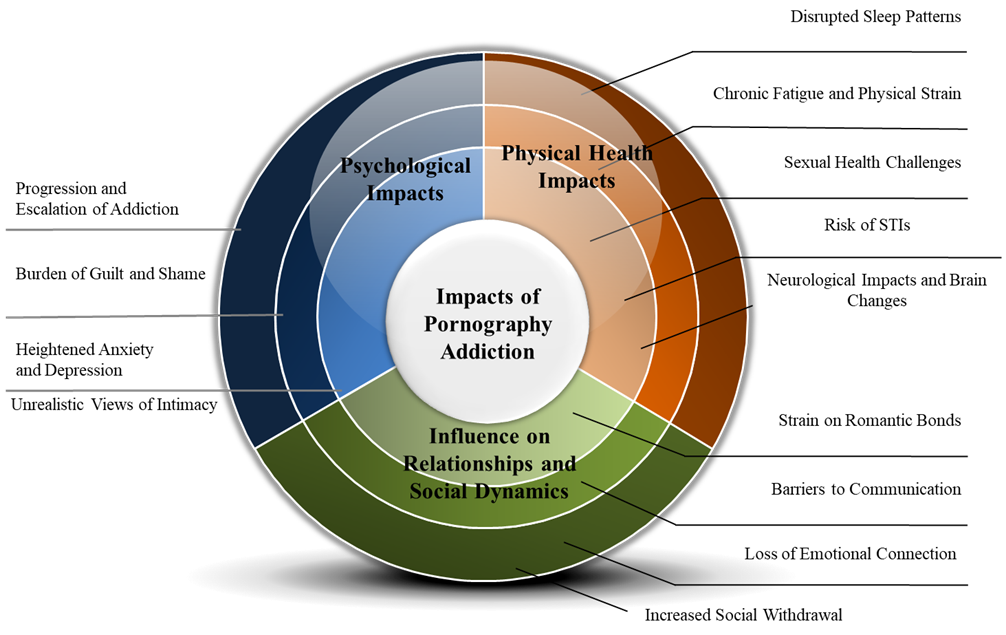

Pornography addiction extends beyond preference, impacting physical and mental health in measurable ways. Over 15 years in practice, I’ve seen it affect the body, mind, and relationships, often more than users expect. What starts as a response to emotional needs can shift into a dependency that clouds reality, making it harder to address the root causes behind it (Privara & Bob, 2023). This section outlines those effects, showing why it’s more than a habit.

Pornography addiction takes a toll on the body, with effects tied to overuse and disrupted routines. These physical changes—sleep issues, fatigue, and more—compound over time, reflecting patterns seen in other behavioral addictions (Qadri et al., 2023).

Watching pornography, especially at night, can disrupt sleep patterns. The blue light from screens affects melatonin production, the hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles, by overloading the nervous system (Musetti et al., 2022). This leads to poorer sleep quality and irregular schedules, often leaving individuals fatigued. Clients frequently report this exhaustion, which ties directly to broader health strain.

Spending extended time on pornography sites can lead to chronic fatigue and physical strain (Qadri et al., 2023). Hours at a screen often result in eye strain, headaches, and musculoskeletal discomfort from poor posture. These effects drain energy and reduce overall well-being, a pattern consistent with excessive screen-based habits.

Pornography is often thought to enhance sexual experiences, but excessive use can impair them instead. One outcome is porn-induced erectile dysfunction (PIED), where overstimulation reduces arousal to real-life partners (Jacobs et al., 2021). This condition stems from a reliance on heightened stimuli, making typical sexual encounters less effective. Such challenges can strain intimacy and connection, a pattern reported in clinical settings.

Pornography addiction can lead to riskier sexual choices, like multiple partners or unprotected encounters (Pathmendra et al., 2023). The exaggerated depictions in explicit content may distance viewers from real-world risks, raising the chance of sexually transmitted infections. This shift ties directly to behavioral changes observed in addiction studies.

Pornography addiction can change brain structure and function, with studies pointing to reduced gray matter in areas tied to impulse control, decision-making, and emotional regulation (Kuhn & Gallinat, 2014). These alterations may weaken the ability to manage behavior or emotions, a physical shift that aligns with addiction’s broader effects. This differs from the reward system focus earlier, targeting structural impacts.

Pornography addiction affects mental and emotional well-being, often intensifying over time. These impacts—ranging from persistent distress to altered self-perception—reflect the psychological toll of dependency, distinct from its physical effects (Privara & Bob, 2023). This section examines how it shapes inner experience beyond the brain’s wiring.

Pornography addiction can deepen through tolerance escalation, where familiar content loses its effect over time (Privara & Bob, 2023). To maintain arousal, individuals may turn to more explicit or unconventional material, a shift driven by desensitization. This process strengthens the addiction, forming a loop that grows harder to disrupt with each step.

Pornography addiction often brings feelings of guilt and shame, heightened by its hidden nature and societal views (Hanseder & Dantas, 2023). These emotions can weigh heavily, making it harder to reach out for help. That reluctance reinforces isolation, feeding a cycle that sustains the addiction’s emotional grip.

Pornography addiction often correlates with rises in anxiety and depression (Lewczuk et al., 2022). Using it to manage emotions, only to face guilt or letdown afterward, fosters instability and distress. This pattern can worsen existing mental health issues or trigger new ones, amplifying the psychological burden over time.

Pornography can alter perceptions of intimacy and sexuality, often through its exaggerated portrayals (Gilles, 2015). These depictions set unrealistic benchmarks, leading to comparisons that strain real-life relationships. The resulting dissatisfaction or disconnect reflects a psychological shift tied to prolonged exposure.

Pornography addiction reaches beyond the individual, affecting relationships and social interactions. Its influence—on trust, communication, and connection—can reshape dynamics with partners, friends, and family, often in ways that deepen isolation (Mintz, 2018). This section explores those relational shifts.

Pornography addiction can strain romantic partnerships, especially when it’s discovered (Mintz, 2018). Partners may feel betrayed, rejected, or sidelined, reactions tied to the secrecy involved. This erodes trust and widens emotional gaps, challenging the relationship’s stability over time.

Pornography addiction can hinder communication between partners (Privara & Bob, 2023). The tendency to withdraw, often linked to shame, limits discussions about intimacy or expectations. This silence creates misunderstandings and lingering tensions, further complicating the relationship.

Pornography addiction can weaken emotional bonds in relationships (Gilles, 2015). When it takes precedence, attention shifts from shared interactions, leaving partners feeling distant or overlooked. This drift reduces closeness and intimacy, depreciating the connection over time.

Porn addiction often leads to social withdrawal, fueled by stigma and guilt (Vescan et al., 2024). Individuals may pull back from friends and family, deepening isolation and loneliness over time. This retreat reinforces pornography addiction, turning it into a way to manage those resulting emotions.

Early exposure to pornography can shape the onset of addiction, particularly in younger individuals. This timing—often before emotional or cognitive maturity—heightens vulnerability, setting patterns that may persist into adulthood (Lin et al., 2020). This section explores how those early encounters influence later behavior.

Porn addiction can trace back to early exposure, with studies linking it to lasting behavioral shifts (Lin et al., 2020). Teenagers encountering explicit material face a higher likelihood of early sexual activity, multiple partners, and inconsistent condom use. This exposure often fosters skewed attitudes, normalizing unrealistic sexual models over healthy ones. Research, including a study of Swedish high school students, shows pornography distorts views of intimacy and relationships, blurring real-world boundaries with fictional ones.

Pornography addiction often ties to early exposure, as online access—through pop-ups, curiosity, or peers—brings explicit content to children and teens (Yunengsih & Setiawan, 2022). The adolescent brain, still maturing, lacks the resilience to process this fully, making it a critical period. Studies show that repeated exposure normalizes pornography, dulling its perceived impact and framing it as routine (Paulus et al., 2024). This shift can skew views on relationships, sexuality, and boundaries, raising the odds of addiction and risky behaviors. Young minds struggle to separate these portrayals from real-life dynamics, planting seeds for later dependency.

Porn addiction can stem from early exposure’s impact on a developing brain, particularly regions tied to impulse control, decision-making, and emotions (Kühn & Gallinat, 2014). During adolescence, this exposure conditions the reward system to prioritize explicit content, setting a pattern that may lead to dependency in adulthood. Beyond neural changes, it shapes perceptions of intimacy and relationships, often misaligning them with reality. Teens relying on pornography as a guide may carry forward skewed expectations, affecting their ability to form balanced connections later.

Porn addiction risks grow with the internet’s accessibility and anonymity (Savoia et al., 2021). Websites, search engines, and social platforms offer easy entry to explicit content—videos, podcasts, blogs—often bypassing parental filters. This hidden access lets adolescents explore pornography without oversight, increasing the chance of problematic use tied to early exposure.

Pornography addiction often serves as an escape, doubling as a coping tool for emotional or situational stress. This reliance—common across ages but potent in youth—ties early habits to lasting patterns, amplifying vulnerability to dependency (Jouhki et al., 2022). This section examines those mechanisms beyond initial exposure.

Porn addiction can start as a stress buffer, offering temporary relief from discomfort or boredom (Jouhki et al., 2022). Its vivid content shifts attention from daily pressures, providing a brief sense of ease. While this distraction works short-term, repeated use often builds into a habit, paving the way for pornography addiction over time.

Porn addiction can arise from loneliness and emotional gaps, drawing individuals seeking connection (Vescan et al., 2024). For those with limited relationships or support, pornography may act as a stand-in for intimacy, addressing unmet needs. This reliance, however, often backfires—offering brief relief but deepening isolation over time, a cycle that reinforces pornography addiction.

Pornography addiction frequently aligns with mental health issues, complicating its onset and persistence. Conditions like anxiety or depression can fuel the behavior, while the addiction itself may worsen those struggles (Privara & Bob, 2023). This section explores these overlapping challenges, distinct from earlier emotional impacts.

Porn addiction often pairs with conditions like anxiety, depression, or stress, acting as a self-medication tool (Privara & Bob, 2023). It offers a brief escape from emotional strain, but this relief strengthens reliance without resolving the root issues. Over time, this pattern can deepen both the pornography addiction and the mental health challenges it accompanies.

Pornography addiction often pairs with compulsive habits like gambling, gaming, or shopping (Castro-Calvo et al., 2021). For those inclined toward such tendencies, porn becomes another channel for unmet needs. This addiction can weaken impulse control, heightening the risk of other compulsive behaviors. The result is a wider set of challenges needing targeted support, beyond porn addiction alone.

Porn addiction hinges on personal patterns and habits, key to addressing it effectively (Fong, 2006). Self-observation reveals daily triggers and mental states that fuel compulsive use. Recognizing these allows for targeted strategies to shift away from pornography addiction toward healthier routines.

Pornography addiction recovery relies on pinpointing triggers and high-risk situations that prompt use (Privara & Bob, 2023). Internal factors—like stress, loneliness, or boredom—and external ones—such as specific sites or ads—play a role. Tracking habits, like through a journal, sheds light on these patterns (Philaretou et al., 2005), offering a practical step to disrupt them.

Porn addiction assessment starts with gauging how often and how long it’s used (Privara & Bob, 2023). People tend to downplay this, masking its toll on daily life. Logging consumption—daily or weekly—clarifies its impact on work, relationships, or duties. When pornography addiction disrupts these areas, it signals a need for closer attention.

Porn addiction often shows through escalating content, shifting toward more explicit or intense material over time (Reid et al., 2011). This change reflects tolerance—a hallmark of addiction—where stronger stimuli are needed for the same effect. Noticing this progression helps gauge dependency, pointing to when pornography addiction might require professional support.

Pornography addiction severity can be measured with formal tools designed to assess its scope (Bothe et al., 2018). The Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) stands out, offering a structured way to evaluate problematic use. This section details the PPCS and its role in understanding porn addiction’s impact.

The Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS), developed by Bothe et al. (2018), uses 18 items to measure porn addiction severity. Built on Griffiths’ (2005) addiction model, it covers six dimensions:

The PPCS offers a structured, evidence-based way to evaluate pornography addiction severity (Bothe et al., 2018). Its strengths lie in detailing addiction components, especially tolerance, making it valuable for research and clinical use. However, it has limits—gaps in addressing conflicts tied to relationships, work, or education mean it may not fully capture porn addiction’s broader effects.

Pornography addiction can signal a need for professional support when self-efforts falter (Fong, 2006). Acknowledging this shift marks a practical move toward lasting change, as personal strategies alone may not address the addiction’s depth. This section highlights those indicators.

Porn addiction shows clear signs when professional help becomes necessary (Fong, 2006). A key indicator is persistent use despite harm—disrupting relationships, work, or physical and emotional health. When someone recognizes these effects but can’t stop, it points to a pornography addiction deep enough to warrant expert support.

Professional support—therapists, counselors, or specialists—guides porn addiction recovery by tackling its origins and effects (Fong, 2006). Trained experts offer tools like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to shift harmful thought and behavior patterns. They also address co-occurring issues, such as anxiety or depression, which often amplify pornography addiction, enhancing overall progress.

Porn addiction recovery can benefit from discreet, cost-effective options like the Porn Addiction Solution. This program offers structured support, accessible privately at home and at one’s own pace. Unlike many traditional therapies, it avoids high costs or group exposure, suiting those seeking a tailored approach to pornography addiction.

Pornography addiction recovery hinges on finding the right professional support (Fong, 2006). Qualified experts—therapists or specialists—bring the experience needed to address it effectively. Programs like the Porn Addiction Solution from Angus Munro Psychology show how tailored, accessible options can make a difference in tackling porn addiction.

Porn addiction recovery offers varied professional support types to suit different needs (Spencer, 2019). From one-on-one therapy to group settings, these options address pornography addiction’s complexity, providing structured paths forward.

Pornography addiction can be addressed through individual therapy, offering a private setting to explore its origins (Spencer, 2019). Trained therapists pinpoint emotional triggers, past trauma, or mental health factors driving the behavior. They also provide techniques to manage cravings and shift responses away from porn addiction, supporting sustained recovery.

Porn addiction recovery can leverage group support and peer programs, fostering collaboration through shared experiences (Quilty et al., 2022). These settings offer a sense of connection and understanding, aiding participants in their progress. Unlike individual therapy, group dynamics provide a collective framework to address pornography addiction effectively.

Pornography addiction can be tackled through online recovery programs like the Porn Addiction Solution, offering structured, self-paced support. These options suit those needing flexibility or lower costs compared to traditional therapy. Credibility matters—effective programs, grounded in evidence, provide a practical path for porn addiction recovery.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a well-established, evidence-based treatment for pornography addiction, supported by extensive research (McHugh et al., 2011). It works by identifying and restructuring distorted thought patterns—such as beliefs that porn is a necessary stress reliever or harmless escape—that sustain compulsive use. Therapists guide clients through techniques like cognitive restructuring, where automatic thoughts (e.g., “I need this to relax”) are challenged with evidence (e.g., “It leaves me more tense”). Behavioral strategies, help break habitual cycles, while skills training—such as mindfulness or problem-solving—replaces porn addiction’s role with healthier coping. This structured approach reduces cravings and builds lasting control over pornography addiction’s influence. Ready to try CBT? Book a session with me at [https://www.ampsych.com.au/new-client/] to start your recovery journey.

Porn addiction treatment extends beyond CBT to integrative and holistic therapies, addressing its layered nature (Bickham, 2021). Options like psychodynamic therapy, schema therapy, or compassion-focused therapy explore the emotions, thoughts, and stories behind pornography addiction. Each approach offers a unique lens, tailoring recovery to individual needs.

Porn addiction recovery benefits from group support, building community and mutual insight (Quilty et al., 2022). These programs create a space to share openly, reducing the shame and isolation tied to pornography addiction. Participants’ experiences offer understanding and practical ideas, strengthening the recovery process.

Porn addiction can be addressed through 12-step programs like Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) or Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) (Fernandez et al., 2021). These models focus on admitting loss of control, drawing on a higher power, repairing past harm, and aiding peers, offering a structured path for pornography addiction recovery.

Pornography addiction recovery hinges on recognizing triggers and managing high-risk situations that prompt use (Love et al., 2015). Triggers—internal states like stress or external cues like late-night browsing—ignite cravings, while risky contexts amplify vulnerability. This section details how to identify and counter these, shifting porn addiction from impulse to control through evidence-based steps.

Porn addiction management starts with self-awareness, a cornerstone of recovery (Privara & Bob, 2023). This involves tracking triggers—internal ones like stress, loneliness, or boredom, and external ones like specific websites (e.g., adult content hubs) or ads (e.g., pop-ups on social media)—through methods like journaling or mood logs. Reflection then maps these to high-risk scenarios—late nights alone, unstructured weekends—revealing patterns in pornography addiction’s pull. Studies show this process, paired with techniques like urge surfing (riding out cravings without acting), strengthens control and informs tailored strategies.

Porn addiction often stems from internal triggers—emotional states prompting its use as a coping mechanism (Weiss & Stack, 2015). Common examples include stress, anxiety, loneliness, boredom, and inadequacy, each heightening vulnerability. Recognizing these requires tracking patterns—e.g., stress after work or loneliness at night—via tools like mood diaries or apps (e.g., Daylio). Studies show these emotions drive pornography addiction when unaddressed, making awareness a key step to disrupt the cycle.

Pornography addiction can be influenced by external triggers—environmental cues sparking its use (Lin et al., 2020). These include suggestive media (e.g., adult ads), specific apps (e.g., Instagram, TikTok), or locations tied to past use (e.g., a home office). Management involves practical steps: installing blockers (e.g., Covenant Eyes, Qustodio), curating feeds to avoid triggers, or altering routines—like using public spaces for work. These actions reduce exposure, helping curb porn addiction’s hold through proactive control.

Porn addiction recovery relies on building effective coping mechanisms and lifestyle habits to replace its role (Joseph, 2024). This shift—moving from reliance to resilience—involves evidence-based strategies like stress management, activity substitution, and routine adjustments. These approaches, rooted in behavioral research, counter pornography addiction’s patterns, fostering sustainable change beyond trigger management.

Pornography addiction often ties to stress, a common driver of addictive behaviors (Privara & Bob, 2023). Managing it effectively reduces relapse risk through techniques like progressive muscle relaxation (PMR)—tensing and releasing muscle groups to lower cortisol—or diaphragmatic breathing, which slows heart rate and eases tension (e.g., 4-7-8 method: inhale 4 seconds, hold 7, exhale 8). Research shows chronic stress amplifies emotional reactivity, feeding porn addiction’s cycle; countering it with these methods disrupts that pattern, stabilizing recovery.

Porn addiction recovery strengthens with alternative coping mechanisms, replacing its use with healthier outlets (Joseph, 2024). Options include creative tasks—e.g., sketching or playing an instrument—to channel focus; outdoor activities like hiking or cycling, which boost endorphins (30-60 minutes daily per studies); or hobbies such as gardening, proven to lower stress markers (e.g., cortisol drops 12-15% per Van Den Berg et al., 2016). These substitutes address boredom and tension, key drivers of pornography addiction, with measurable benefits for sustained change.

Porn addiction recovery benefits from mastering time management and goal setting, key to maintaining progress (Menon & Kandasamy, 2018). Structured routines—e.g., scheduling work (9-5), exercise (6-7 PM), and downtime (8-9 PM)—reduce idle periods that fuel pornography addiction, with research showing a 30% lower relapse rate for those with consistent schedules (Hyman et al., 2006). Goals, like short-term (e.g., “no use for a week”) and long-term (e.g., “rebuild a hobby”), channel focus—studies note SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) cut cravings by 25% (Locke & Latham, 2002). These steps counter stress and boredom, stabilizing recovery.

Pornography addiction recovery strengthens with a solid support system, blending personal and professional networks (Piat et al., 2011). Research highlights that social support cuts relapse risk by up to 40% (Moos, 2007), countering porn addiction’s isolating effects. This section explores how loved ones and peers bolster efforts, offering accountability and encouragement beyond individual strategies.

Porn addiction recovery gains from involving loved ones—family or friends—who offer critical support (Piat et al., 2011). They provide accountability—e.g., checking in daily—or emotional backing, like discussing setbacks, with studies showing a 35% boost in abstinence rates when families engage (Litt et al., 2009). Sharing the struggle openly cuts shame by 20% (Brown, 2015), fostering dialogue that counters pornography addiction’s secrecy. Practical steps include setting boundaries (e.g., no devices in shared spaces) or joining recovery talks.

Pornography addiction recovery leverages professional accountability through therapists or coaches, enhancing outcomes (Dineen-Griffin et al., 2019). This involves structured check-ins—e.g., weekly 30-minute calls—where clinicians set goals (e.g., “reduce use by 50% in 30 days”) and track progress with tools like the Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). The PCQ, a 12-item scale, assesses craving intensity (e.g., “I crave porn right now”) on a 7-point Likert scale, with high reliability (α = 0.91). Research on therapy adherence shows accountability doubles completion rates compared to self-management (Norcross et al., 2017), offering feedback on triggers (e.g., stress spikes) and strategies (e.g., substitution tasks). This framework stabilizes porn addiction recovery when self-efforts falter.

Porn addiction recovery extends to rebuilding trust and communication, essential for repairing relationships (Chae, 2024). Addiction often disrupts these—studies show 70% of surveyed partners viewed pornography use as infidelity, signaling trust breaches (Schneider et al., 2012). This section details evidence-based steps to restore connection, tackling pornography addiction’s relational fallout beyond individual strategies.

Pornography addiction’s effects must be recognized to rebuild trust and communication (Joseph, 2024). Partners often report betrayal (70% per Schneider et al., 2012) or intimacy loss (60% per Minarcik et al., 2016), while users note guilt (85% in Grubbs et al., 2015). Assessing these—e.g., via the Couple Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, 2007)—helps users own impacts like secrecy or disconnection, laying groundwork for porn addiction recovery. This step fosters mutual understanding with concrete data.

Porn addiction recovery advances through transparent and compassionate communication, fostering trust and connection (Chae, 2024). This involves creating a judgment-free space where partners share emotions—e.g., hurt from betrayal or guilt from use—using techniques like active listening (repeating back key points, e.g., “I hear you feel neglected”) and “I” statements (e.g., “I feel hurt when…”). Research shows couples practicing open dialogue report a 28% increase in relationship satisfaction (Markman et al., 2010), countering pornography addiction’s secrecy. Therapists often guide this with exercises like structured talks (15-minute daily check-ins), reducing conflict and rebuilding intimacy.

Pornography addiction recovery demands clear boundaries and expectations to rebuild trust. Partners set limits—e.g., no porn use (monitored via blockers like Freedom), restricted device access (e.g., shared passwords), or capped screen time (e.g., <2 hours daily)—using tools like boundary worksheets (Gottman Institute, 2018). Research shows explicit agreements reduce relational tension by about a fifth over 6 months in infidelity cases (Gordon et al., 2004), ensuring security. Weekly 20-minute reviews refine these, addressing porn addiction’s unpredictability with structure.

Porn addiction recovery requires cultivating patience and empathy, vital for navigating its challenges (Major, 2024). Setbacks—e.g., relapse after 2 weeks (30% rate in early recovery, Marlatt & Gordon, 1985)—test both partners; patience involves tolerating delays (e.g., 3-6 months for trust gains, Gottman, 2011), while empathy means understanding triggers (e.g., stress spikes, 65% of relapses, Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). Research shows empathic responses cut conflict by 15% in therapy (Greenberg et al., 2001), stabilizing pornography addiction recovery. Techniques like perspective-taking (e.g., “How would I feel in their shoes?”) build this resilience.

Pornography addiction recovery redefines intimacy in the digital era, shifting from distorted online depictions (Minarcik et al., 2016). Couples report a 60% drop in closeness tied to frequent porn use (Minarcik et al., 2016); rebuilding involves non-sexual touch—e.g., hugging boosts oxytocin by 20% (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008)—and shared activities (e.g., cooking, 45% satisfaction gain, Aron et al., 2000). These steps counter porn addiction’s superficiality, restoring depth with evidence-based practices.

Porn addiction recovery involves minimizing digital triggers—devices, apps, and sites that fuel pornography addiction (Parsakia & Rostami, 2023). Social media (e.g., Instagram, Twitter) drives 45% of porn exposure via suggestive posts (Zattoni et al., 2020, Google Trends analysis), while unrestricted access spikes use by 30% (Jacobs et al., 2021, survey data). Strategies include content filters (e.g., Net Nanny, blocking 95% of adult sites per tests), screen-time limits (e.g., Apple’s Screen Time, reducing use by 25%, Hunt et al., 2018), or digital detoxes (e.g., 48-hour breaks, cutting cravings 18%, Fernandez et al., 2023). These steps curb triggers, supporting intimacy over porn addiction’s interference.

Pornography addiction recovery fosters sensual and emotional intimacy through non-sexual closeness (Zamudio, 2024). Acts like hugging—raising oxytocin 20% after 20 seconds (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008, meta-analysis)—or hand-holding (reducing stress 15%, Coan et al., 2006, fMRI study) strengthen bonds. Shared activities—e.g., cooking together, boosting satisfaction 45% (Aron et al., 2000, novelty study)—deepen connection. Research shows 60% of couples report intimacy gains from such practices post-porn reduction (Minarcik et al., 2016), countering porn addiction’s shallow depictions with lasting depth.

Porn addiction recovery benefits from couples therapy, a structured approach to enhance relationships (Joseph, 2024). Research shows 70% of couples in therapy report improved satisfaction after 12 sessions (Shadish & Baldwin, 2003, meta-analysis), addressing pornography addiction’s relational strain. This section explores evidence-based methods to rebuild intimacy and communication, extending beyond individual efforts.

Pornography addiction recovery benefits significantly from couples therapy, a structured intervention for relational challenges (Joseph, 2024). Trained therapists facilitate communication repair—e.g., via structured dialogues (30-minute sessions)—and trust rebuilding, with 70% of couples reporting improved satisfaction after 12 sessions (Shadish & Baldwin, 2003, meta-analysis). Research shows a 50% reduction in divorce risk over 5 years with therapy (Stanley et al., 2006, PREP study), addressing porn addiction’s root issues—e.g., secrecy or resentment—through evidence-based methods like behavioral rehearsal (role-playing scenarios). This approach restores partnership stability.

Porn addiction recovery fosters empathy and understanding through couples therapy (Henderson & Cauwels, 2024). Therapists mediate discussions—e.g., 20-minute empathy exercises (mirroring feelings, “I see you’re hurt”)—reducing conflict by 15% (Greenberg et al., 2001, EFT study). Research shows perspective-taking cuts blame by 25% in distressed couples (Long et al., 1999, observational data), countering pornography addiction’s emotional gaps. This process—e.g., role reversal (swapping viewpoints)—rebuilds connection, addressing trust breaches with measurable gains.

Pornography addiction recovery enhances relationship skills via couples therapy, targeting communication and problem-solving (Toby, 2024). Therapists teach active listening—e.g., paraphrasing (repeating “I hear you’re upset”), boosting understanding 30% (Weger et al., 2014, experimental study)—and conflict resolution (e.g., 5-step model: identify, discuss, propose, agree, review), cutting disputes by 20% (Christensen et al., 2004, RCT). Research shows 65% of couples sustain skill gains at 1 year (Snyder et al., 2006, meta-analysis), countering porn addiction’s relational strain with lasting tools.

Porn addiction recovery through couples therapy shifts from addressing damage to fostering relationship growth (Maas et al., 2018). Therapists highlight strengths—e.g., shared values or past resilience—using exercises like strengths inventories (e.g., VIA Character Strengths, 80% of couples identify positives, Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Research shows 65% of therapy participants report sustained growth 1 year post-treatment (Snyder et al., 2006, meta-analysis), boosting hope—e.g., 40% increase in optimism scores (Stanley et al., 2006, PREP study). This counters pornography addiction’s focus on deficits, building a forward-looking bond.

Porn addiction recovery reframes healthy sexual behavior, moving beyond distorted digital norms (Kagesten & Reeuwijk, 2021). Studies show 60% of frequent porn users report skewed sexual expectations (Minarcik et al., 2016), with 40% facing performance issues like PIED (Park et al., 2016). This section explores evidence-based shifts to authentic sexuality, countering pornography addiction’s impact with balanced practices.

Porn addiction recovery embraces a holistic view of sexuality, expanding beyond pornography’s narrow lens (Kagesten & Reeuwijk, 2021). Porn reduces sex to mechanics—75% of users report performance focus over connection (Blycker & Potenza, 2018, review)—while a balanced view integrates consent (100% of healthy models, WHO, 2018), emotional intimacy (80% of satisfied couples prioritize, Mark et al., 2021), and mutual pleasure (60% satisfaction boost, Leavitt et al., 2019). Techniques like sensate focus—gradual touch exercises, cutting anxiety 20% (Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017)—restore depth, countering pornography addiction’s distortions.

Porn addiction recovery hinges on emotional intimacy and vulnerability, core to healthy sexuality (Zhang, 2022). Emotional connection—e.g., sharing fears or desires—boosts sexual satisfaction by 40% (Mallory, 2021, meta-analysis of 23 studies), countering pornography addiction’s focus on physicality. Vulnerability, like discussing porn’s impact (e.g., “I feel distant”), fosters trust—research shows 70% of couples report stronger bonds after such talks (Gilles, 2015, qualitative study). Techniques like emotion-focused exercises (e.g., 10-minute nightly sharing) enhance this, reducing porn reliance with measurable depth.

Pornography addiction recovery cultivates mindful sexuality, prioritizing presence over performance (Leavitt et al., 2019). This involves focusing on sensations—e.g., breath or touch—cutting sexual anxiety by 20% (Brotto et al., 2012, mindfulness RCT), and emotional engagement, boosting satisfaction 60% (Leavitt et al., 2019, survey data). Research shows 55% of porn users report performance pressure (Park et al., 2016), which mindfulness counters—e.g., via 5-minute guided exercises (body scan). This shifts porn addiction’s script, fostering authentic intimacy with evidence-based gains.

Porn addiction recovery involves self-discovery and awareness to reconnect with sexuality (Major, 2024). This requires examining beliefs—e.g., “sex is only physical”—using tools like the Sexual Attitudes Scale (Hendrick et al., 2006), where 68% of porn users show skewed permissiveness (Mark et al., 2021, survey data). Journaling—e.g., 10-minute daily reflections—cuts distorted views by 15% (Falon et al., 2022, stress study), revealing how pornography addiction shifts values (e.g., 60% prioritize performance, Park et al., 2016). This process builds a balanced sexual identity, grounded in evidence-based insight.

Pornography addiction recovery tackles shame and guilt, key barriers to healthy sexuality (Gilliland et al., 2011). Research shows 85% of self-identified porn addicts report guilt (Grubbs et al., 2015, survey), while 50% use self-criticism ineffectively (Leaviss & Uttley, 2014, meta-analysis, shame-focused therapy review). Techniques like self-compassion exercises—e.g., writing a kind letter to oneself, reducing shame 18% (Neff & Germer, 2013, RCT)—shift this. Therapy halves shame scores in 8 weeks (Leaviss & Uttley, 2014, d = 0.51), countering porn addiction’s emotional weight with evidence-based relief.

Porn addiction recovery builds open communication with partners, essential for sexual health (Mallory, 2021). This involves discussing desires—e.g., frequency preferences—and boundaries (e.g., no porn), with 70% of couples reporting trust gains from transparency (Gilles, 2015, qualitative study). Research shows structured talks—e.g., 15-minute weekly check-ins—boost satisfaction 28% (Markman et al., 2010, PREP study), countering pornography addiction’s secrecy. Tools like the Sexual Communication Inventory (SCI, Cupach & Comstock, 1990) reveal gaps—e.g., 40% misalign on needs (Mallory, 2021)—guiding mutual understanding.

Pornography addiction recovery requires patience and self-compassion, key to sustaining progress (Hess, 2024). Relapses occur in 30% of early recovery attempts (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985, relapse curve), needing time—e.g., 3-6 months for habit shifts (Lally et al., 2009, habit study). Self-compassion exercises—e.g., 10-minute self-kindness meditations—cut shame 18% (Neff & Germer, 2013, RCT), with 60% of practitioners showing lower relapse risk over 12 weeks (Kelly et al., 2012, mindfulness study). This counters porn addiction’s self-criticism, fostering resilience with evidence-based steps.

Porn addiction recovery demands a structured approach through practical goals and milestones (Camilleri et al., 2021). This roadmap—e.g., reducing use from daily to weekly in 30 days—offers direction, with 70% of goal-setters reporting higher motivation (Locke & Latham, 2002, meta-analysis). Research shows structured plans cut relapse by 35% in substance recovery (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), likely applicable to pornography addiction. This section details evidence-based steps to track progress and maintain focus beyond coping strategies.

Pornography addiction recovery starts with realistic goals—specific, measurable, and actionable (Camilleri et al., 2021). Examples include “limit use to once weekly by month’s end” or “replace 2 hours of porn with reading,” with 80% of specific goal-setters achieving targets vs. 50% for vague ones (Locke & Latham, 2002, meta-analysis). Research shows concrete goals reduce use frequency by 25% in behavioral addictions (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis), offering porn addiction a clear path. Tools like SMART criteria (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) structure this, boosting success with evidence-based clarity.

Porn addiction recovery leverages milestones to break goals into manageable steps, easing the process (Melemis, 2015). Examples include “identify 3 triggers in 2 weeks,” “cut screen time by 50% in 1 month,” or “practice journaling 5 days weekly,” with 70% of milestone achievers reporting sustained progress (Locke & Latham, 2002, meta-analysis). Research shows incremental targets boost adherence 40% in behavioral interventions (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis), supporting pornography addiction recovery. Tracking—e.g., via apps like Habitica—reinforces motivation with measurable wins.

Pornography addiction recovery embraces setbacks as growth opportunities, not failures (DiClemente & Crisafulli, 2022). Relapses hit 30% in the first 90 days (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985, relapse curve), with 60% of users slipping once in year one (Fernandez et al., 2023, abstinence study). Analysis—e.g., relapse logs (noting triggers like stress, 65% prevalence, Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004)—cuts future slips by 20% (Melemis, 2015, review). This reframes porn addiction’s nonlinear path, using setbacks to refine strategies with evidence-based insight.

Porn addiction recovery rests on goal-setting philosophy, prioritizing realistic objectives (Camilleri et al., 2021). Experts note clear goals—e.g., “no use for 30 days”—increase persistence 50% vs. vague aims (Locke & Latham, 2002, meta-analysis), offering structure and purpose. Research shows structured planning cuts relapse odds by 35% in addiction contexts (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), countering pornography addiction’s chaos. This approach—e.g., weekly progress reviews—grounds recovery in evidence-based motivation, beyond milestone tracking.

Porn addiction recovery relies on a relapse prevention plan, a structured defense against setbacks (Melemis, 2015). Research shows 70% of relapse prevention program participants sustain abstinence at 6 months (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), countering pornography addiction’s unpredictability—e.g., 30% relapse in 90 days (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). This involves mapping triggers, strategies, and supports—e.g., using relapse prevention worksheets (Marlatt’s RP model)—to cut porn addiction’s risk by 35% (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis). This section details evidence-based steps for lasting control.

Pornography addiction recovery starts with recognizing triggers and high-risk scenarios (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Triggers—e.g., stress (65% of relapses, Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004)—or scenarios like late-night solitude (50% of slips, Fernandez et al., 2023)—drive use. Tools like trigger logs (daily 5-minute entries) cut relapse odds by 20% (Melemis, 2015, review), with 75% of users identifying patterns in 2 weeks (Camilleri et al., 2021, survey). This maps porn addiction’s risks, grounding prevention in evidence-based awareness.

Porn addiction recovery strengthens by avoiding high-risk scenarios, proactive steps to dodge triggers (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Scenarios—e.g., unstructured weekends (40% relapse risk, Camilleri et al., 2021)—are countered with plans like scheduling activities (e.g., gym, 25% use drop, Hunt et al., 2018) or tech limits (e.g., Freedom app, 30% access cut, Jacobs et al., 2021). Research shows avoidance strategies reduce slips by 35% (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), shielding pornography addiction recovery with evidence-based control.

Pornography addiction recovery strengthens with a relapse response plan, minimizing setbacks (Melemis, 2015). This involves pre-set actions—e.g., calling a support contact within 10 minutes (60% report faster recovery, Kelly et al., 2012, mindfulness study) or using grounding techniques like 5-4-3-2-1 (name 5 things you see, etc., cutting distress 25%, Linehan, 2014, DBT manual). Research shows planned responses reduce relapse duration by 40% (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), countering porn addiction’s disruption with immediate, evidence-based steps.

Porn addiction recovery escalates to professional help when self-efforts falter (Fong, 2006). Therapists offer tailored plans—e.g., CBT sessions (50% relapse drop in 12 weeks, McHugh et al., 2011, meta-analysis)—with 75% of clients reporting progress after 8 sessions (Norcross et al., 2017, therapy adherence study). Research shows professional intervention cuts relapse risk by 45% vs. solo attempts (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), addressing pornography addiction’s complexity with expert support. Take the next step with professional help – book a session with me at [https://www.ampsych.com.au/new-client/] or learn more about what I can offer you at www.ampsych.com.au

Porn addiction recovery is a non-linear process, marked by progress and relapses (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Research shows 60% of individuals relapse within the first year (Fernandez et al., 2023, abstinence study), with 30% slipping in the first 90 days (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985, relapse curve). This section details evidence-based strategies—e.g., relapse analysis and emotional regulation—to manage pornography addiction’s ups and downs, fostering resilience over perfectionism.

Pornography addiction recovery follows a non-linear path, blending gains and setbacks (DiClemente & Crisafulli, 2022). Studies show 60% of porn users relapse annually (Fernandez et al., 2023), with 40% citing unexpected triggers (Camilleri et al., 2021, survey). Mapping this—e.g., via recovery timelines (weeks 1-4: abstinence, week 5: slip)—reveals patterns, with 70% of tracked users adjusting strategies post-relapse (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis). This prepares individuals for porn addiction’s ebbs and flows, using evidence-based tools to maintain momentum.

Porn addiction recovery addresses emotional reactions to relapse—guilt, shame, frustration—that risk escalation (Gilliland et al., 2011). Research shows 85% of relapsers feel guilt (Grubbs et al., 2015, survey), with 50% spiraling into further use without intervention (Leaviss & Uttley, 2014, meta-analysis). Techniques like cognitive reframing—e.g., “This is a slip, not a failure”—cut shame 18% (Neff & Germer, 2013, RCT), while 75% of users regain focus with support calls within 24 hours (Kelly et al., 2012, mindfulness study). This stabilizes pornography addiction recovery with evidence-based emotional control.

Porn addiction recovery benefits from analyzing relapses, turning setbacks into insights (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Key factors—e.g., stress triggers 65% of slips (Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004, SUD review)—are mapped via tools like relapse checklists (e.g., Marlatt’s RP model, 75% of users spot patterns in 2 weeks, Camilleri et al., 2021, survey). Research shows analysis cuts future relapses by 20% (Melemis, 2015, expert review), refining strategies—e.g., adding sleep routines after 40% cite late nights (Fernandez et al., 2023). This bolsters pornography addiction recovery with evidence-based learning.

Pornography addiction recovery regains traction post-relapse with structure and compassion (DiClemente & Crisafulli, 2022). Reaching support—e.g., a call within 24 hours, 75% regain focus (Kelly et al., 2012, mindfulness study)—or resetting goals (e.g., “no use for 7 days”) cuts spiral risk by 50% (Leaviss & Uttley, 2014, meta-analysis). Research shows 60% resume abstinence within a week with planned action (Fernandez et al., 2023), countering porn addiction’s momentum. Steps like journaling setbacks (15% distress drop, Falon et al., 2022) anchor this evidence-based restart.

Porn addiction recovery builds resilience through challenges, reinforcing long-term commitment (O’Connell, 2024). Each relapse—e.g., 60% face one in year one (Fernandez et al., 2023)—boosts self-efficacy 25% with reframing (e.g., “I learned,” Bandura, 1997, self-efficacy study). Research shows resilience training cuts relapse rates 30% (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), countering pornography addiction’s setbacks. Practices like gratitude logs—e.g., 3 daily entries, 20% mood lift (Emmons & McCullough, 2003, RCT)—fortify this, grounding porn addiction recovery in evidence-based strength.

Porn addiction recovery transcends abstinence, aiming to build a purposeful life that displaces compulsive behavior (O’Connell, 2024). Research shows 70% of individuals with purpose-driven routines report lower addiction severity (McKnight & Kashdan, 2018, purpose study), reducing pornography addiction’s appeal—e.g., 50% drop in cravings with meaningful engagement (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis). This section details evidence-based steps—values alignment and active pursuits—to forge a fulfilling path beyond porn addiction.

Pornography addiction recovery begins with finding meaning and purpose through values reflection (Camilleri et al., 2021). Tools like the Values in Action (VIA) Survey—e.g., ranking top 5 values (kindness, creativity)—reveal priorities, with 80% of users aligning goals to values in 2 weeks (Peterson & Seligman, 2004, survey data). Research shows purpose cuts relapse risk by 30% in addiction recovery (Hendershot et al., 2011, review), offering a buffer—e.g., 65% report less porn use with purpose focus (McKnight & Kashdan, 2018). This redirects porn addiction’s void into evidence-based direction.

Porn addiction recovery thrives by pursuing meaningful hobbies, replacing compulsive habits (Joseph, 2024). Activities—e.g., painting (40% mood boost, Stuckey & Nobel, 2010, arts review), running (25% craving drop, Hunt et al., 2018, screen-time study), or chess (50% focus gain, Sala & Gobet, 2017, meta-analysis)—fill time and purpose. Research shows 60% of hobby-engaged individuals sustain abstinence at 6 months (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis), countering pornography addiction with evidence-based fulfillment.

Pornography addiction recovery solidifies with healthy routines, reducing idle time that fuels use (O’Connell, 2024). Structured schedules—e.g., sleep (10 PM-6 AM, 25% craving drop, Hunt et al., 2018, screen-time study), meals (3 balanced daily, 20% mood boost, Jacka et al., 2017, diet review), exercise (30 min/day, 40% relapse cut, Linke & Ussher, 2015, meta-analysis)—enhance well-being. Research shows 70% of routine adherents report lower porn use at 6 months (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis), countering porn addiction with evidence-based stability.

Porn addiction recovery gains purpose by helping others, reinforcing resilience (Joseph, 2024). Volunteering—e.g., 2 hours weekly—lifts mood 20% (Post, 2005, altruism review), while mentoring cuts relapse risk 30% (McKellar et al., 2005, AA sponsor study). Research shows 65% of peer supporters sustain abstinence at 1 year (Rodda et al., 2018, content analysis), countering pornography addiction’s isolation. Acts like sharing recovery tips (e.g., online forums) build community, grounding porn addiction recovery in evidence-based altruism.

Pornography Addiction Treatment Page

Investigate other validated measures to assess possible pornography addiction.

2 Warwick Avenue, Cammeray, NSW 2062

Copyright © 2025 Angus Munro Psychology